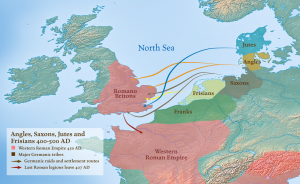

We explore the origins of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians in the North Sea region of northern Europe. The early raids on the coasts of Britain and Gaul set the stage for the later mass migrations. The similarities between the languages of these respective groups are examined.

Map Prepared by Louis Henwood (Click Map for Larger Image)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Pingback: Lecture Notes: Anglo-Saxon England | LIT 231: English Literature to 1800

Interesting episode. I’m Dutch and Frisian, so I recognized many examples. Keep up the good work!

Thanks!

Thanks for this very interesting podcast.

Here’s an example of how close Frisian is to English.

It starts at 3.47.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K1XQx9pGGd0

Thanks!

In Welsh, four is pedwar and five is pump, pronounced like “pimp.” Any idea of that evolution?

I know very little about the evolution of Welsh, but “pedwar” is generally considered to be cognate with English “four” based on a common Indo-European root which has been reconstructed as *kwetwer. And “pump” is considered to be cognate with English “five” and Latin “penta” based on an Indo-European root that has been reconstructed as *penkwe.

Though really Greek has pénte (πέντε) and Latin has quinque, ultimatelty from the Proto-Italic *kwenkwe, which does indeed come from *penkwe.

That’s right. “Pente” is the Greek root, not Latin. (I just researched all of this for “Episode 114: The Craft of Numbering.”)

You must follow Sanatan and sanskirt to know everything

Hello, the map’s linked to the smaller version.

Thanks for the note. It’s fixed now.

Pingback: How was Modern English formed? – The History of English

It’s interesting you should mention the word “dun” – meaning a shade of brown. But you said the word had vanished from the English language. It hasn’t. It is commonly used to refer to a yellowish brown shade of coat found in horses. Also Shakespeare used it in one of his sonnets: “If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun”.

I don’t believe the word is used in English outside the archaic (Shakespeare) and in horses, although it is possible it is used in cattle also.

Yeah, I have received a LOT of emails over the years about the continued use of the word “dun.” I no longer say that a word has vanished or disappeared from English because I am convinced that just about every old word survives somewhere in some regional or local dialect or in some specialized sense.

My mother’s family is southern Appalachian USA since the 1700’s. I remember hearing my grandfather use words (including “dun”) that sounded like uneducated English – which I learned as an adult, was the continuation of the language of the old country. Thanks for this informative and entertaining podcast!

Small dingy brown coloured British birds are often referred to as dun coloured.

Indeed there is a small brown garden bird that is actually called a ‘dunnock’ (brown and small).

There is a small species of sandpiper, common in both the old world and the new, called a Dunlin. My understanding is that the name is due to its drab, gray-brown or tan-brown winter plumage. Not sure what rhe “_lin” part of the name is.

You must follow Sanatan and sanskirt to know everything

Angela, as I wrote elsewhere, dun is used in geology as the root of the name of the rock dunite, named after Dun Mtn., New Zealand. I did the field work for my Masters in east-central Norway on a dunite body. Oddly enough, the dun color is that of the weathered variety. When fresh (i.e., unweathered), dunite is spectacularly bright olive green.

Hi Kevin,

I only discovered your podcast a month back, it is excellent. This episode touched upon something I had pondered a good while – The Jutes! My understanding is that The Danes had taken over northern Jutland by AD200 so these folk would have been speaking Proto-Norse and there is little place name or linguistic evidence in Kent or the Isle of Wight to suggest this was the case. I much prefer the Frankish theory, but then again as you say, who really knows!..

On another point, could you or anyone else help with matter that has perplexed me? I really enjoyed the part of this podcast where you talk about English and Frisian both dropping the g’s in rain and the n’s in goose etc but do you know if this process began before the migration or after it (in other words independently)? I wonder if there is any (scant) evidence either way.

Anyway, brilliant work. Thank you!

There are some place names I have noticed here on the Isle of wight of possible North germanic origin- such as Hulverstone (hulver coming from Middle English and from old norse hulfr for holly), great thorness (Ness meaning headland in norse placenames), among others. Whether this is from later Danish invasions is unclear. If the Jutes did speak proto-norse it would have been influenced a lot by west germanic languages between the time of the initial migration of Jutland and the formation of the angles saxon kingsoms, and proto norse was still very close to proto germanic and west germanic.

There is also a theory that the Jutes were Geats who migrated to Jutland, and there is a little bit of evidence for this. In terms of archeology while it is true that the Jutes had a strong Frankish/Gaulish mark , this may have been due to the facts that Kent was in close proximity to Frankia and may have been under its domain at one point, and that the romano British culture and trade network was not really lost.

But also, there is southern scandinavian archaeological connections found, in forms such as Bracteates, Brooches and coinage.

Hi TJ, thank you for the info. I know Hulverstone as my wife is from the IoW although she was not familiar with The Longstone!

I think you may have nailed it. If the Jutes did arrive around AD450 and were a small contingent in a mass West Germanic speaking group then by the time we have written English those differences would have levelled out. True too that Proto-Norse and Proto-Old English (for want of a better expression) must have been very similar (although I suspect they would have thought “hmmm you sound a bit different to me”!

Agree also regarding the trading links between Kent and the Franks. There must have been some periods of relative calm to allow it to continue.

Hello! I’ve only been introduced to your podcast a few weeks ago. An acquaintance of mine with Scottish roots had posted about episode 157 (257?), so I gave it a listen. My mind was blown and as a lover of both history and words, I have become a huge fan.

I am now on this episode. I have Danish heritage and I was wondering where the word “jute” originated. I don’t know that I caught the explanation in this episode. Perhaps I missed it. Thanks ever so much!

Jute is rather unknown in its origin. One of the possibilities is it meaning a Giant or Jotunn, coming from Eotan, which is the old English word for Jute.

There is also a hypothesis that it is connected to the word Geat and Gautaz, with the Jutes being Geats who migtated to Jutland from Götaland. I find this interesting and there is some evidence for this.

Pingback: Navel-Gazing About The R-DF95 Jutes – Wandering Trees

Thanks Kevin for a fascinating pod cast.. so far I’m only on episode 28 but I find it fascinating and as a lawyer myself I envy you that you have found such a fascinating interest to become expert in.

I’m hoping that in later episodes that you will look at Celtic languages because I am Irish with English as my mother tongue but of course my ancestors all spoke gaelige.

Also I’m hoping that you might look into modelling what languages will emerge from English given the proliferation and influence in media etc of English around the world in the last few centuries.

Thanks again for your great work.

Johnny

Please save me some time and tell me where you cover the switch from “der/die/das” to “the.” This little trick got rid of gender rules for nouns. It seems to me that if anything made English the language that’s taken over the world, it’s not having to memorize genders for nouns (although I understand the Turkish languages do as well). I’d always heard it was the Frisians. But you don’t mention that (or it happened much later) so I guess it wasn’t the Frisians. Who was it and when was it and where do you tell this story? Thanks in advance, I hope.

The loss of grammatical gender took place during the latter part of the Old English period. The Norse influence from the Vikings may have contributed to the change. The topic is discussed in some detail in ‘Episode 53: The End of Endings.’

Dear Kevin, While using the word “the” almost unconsciously in Episode 53 — throughout your explanations of word order and the dropping of inflections such that the Vikings and Anglo Saxons could understand each other, you really don’t mention “the.” My suspicion is that it happened earlier perhaps during those mead-soaked winters enjoyed by the Angles and Saxons which lead to both slurring and vowel and consonant shifts toward the front of the mouth. Or perhaps another time when two languages loaded with gender nouns just slurred together. Are you certain that “the” isn’t much more important? It’s “the” that frees up nouns, verbs, objects, even the bloody infinitive (in Greek) from the memorization of male, female, and neuter with all their exhausting inflections. Why wasn’t it dropped earlier? And why isn’t it more important? If one aspect explains the popularity of English today (the language of finance and technology!) isn’t it the fact that because of our wonderful use of “the,” no speaker of another language has to bother with m/f/n in the first place? Given the choice, our simplification of “the” has rid us of almost all gender nouns and has made English almost everybody’s second language. It’s so natural to live without the weight of all those m/f/n inflections, our dropping them must bear more importance. Doubtless, the sentence structure settling (generally) into subject/verb/object was absolutely necessary. But are you sure that didn’t happen after people just gave up on gender nouns, saying a grateful goodbye to all those inflections and a welcoming hello to “the”?

Fascinating episode! It’s amazing to see how the blend of Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians shaped the English language and culture. The historical insight into their migrations and influences really brought the topic to life. I can’t wait for the next episode!

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed the episode.

Hi Kevin, thanks again for this wonderfully informative podcast! It is very pleasant and interesting to listen to, and I look forward to at least a second listen with a handy notebook. In this episode, you mentioned a couple of other podcasts for more information on the history of England; any recommendations for those interested in deep diving from the time of Indo-Europeans to the Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic tribes? I realize these topics might be more challenging with far fewer written resources, so it may be more of an archeology topic. I guess the stuff I’m really most interested in is the daily lives of people in these early times, such as how foods were prepared, how clothing and footwear was made, shelter, agriculture, seasonal foraging and hunting, and definitely the worldview and mythological belief systems of these groups. Podcasts, books, documentaries, etc., etc., all types of resources are very welcome. Thanks!

What an incredible episode! It’s fascinating to see how the interactions among the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians played a pivotal role in shaping the English language and culture. The deep dive into their migrations and lasting influences made history feel so alive. Looking forward to the next episode!